A number of 19th century artists made visual references to Roseneath on the Derwent River within the current City of Glenorchy. These include Joseph Lycett, George William Evans and James Taylor (no not ‘Sweet Baby James’) all of whom may have a connection with each other as I will explain.

Background to Joseph Lycett

Let’s start with Joseph Lycett who left a significant body of work depicting Sydney and Newcastle in NSW, and a few pieces named with features along the Derwent River.

Lycett didn’t come to Australia by plan. He was a forger and the British government transported him to Sydney with a sentence of 14 years. He arrived in 1814. It was clear he had skills and was almost immediately given a ticket of leave on landing, but he couldn’t help himself. Within 15 months Lycett was illegally printing bank notes for use in NSW. His new sentence was relocation to Newcastle for hard labour in the coal mines. I suspect there must have been something charismatic about this man despite the Australian Dictionary of Biography alleging Lycett had ‘habits of intoxication’ that were ‘fixed and incurable’. Before long his abilities were noted and he was out of the mines and drafting designs for new buildings in Newcastle. In 1821 he was finally pardoned and left Australia for good the following year. But Lycett never visited Van Diemen’s Land.

I wondered how he came to produce the well-known pictorial publication Views of Australia or New South Wales & Van Diemen’s Land, published by John Souter, London, 1824-25 described by eminent Australian Art historian John McPhee as “the most lavish pictorial account of the colony ever produced”. McPhee has come to the conclusion that Lycett couldn’t help being a con man. Though his views of Van Diemen’s Land were supposedly scenes he had witnessed, McPhee (quoted in the Sydney Morning Herald 5/4/2006) says “there’s no doubt he never went there”. We can be surprised to learn that when Views In Australia didn’t sell in England as well as Lycett hoped, he turned to forging bank notes again. He must have loved his printing press!

So I began to research how Lycett ‘knew’ what the Derwent River and the surrounding land looked like.

When Lycett first landed in Sydney, Governor Macquarie was ruling the colony. During Lycett’s sojourn in Newcastle, Macquarie became acquainted with the artist’s pictorial records of the colony. In 1818, the Governor received the personal gift of a chest. Lycett had painted eight of the twelve panels on this chest with views of Newcastle as well as copies of William Westall’s Views of Australian Scenery. In 1820, the year Lycett returned to live in Sydney and earn a living as a painter, according to http://www.nla.gov.au/selected-library-collections/lycett-collection ‘Governor Macquarie and Elizabeth Macquarie were among his patrons’. Obviously impressed, Governor Macquarie sent a selection of the artist’s work to Lord Bathurst, Secretary of State for the Colonies, in England.

But what does this have to do with the Derwent River?

What is the story about Joseph Lycett’s Tasmanian (then named Van Diemen’s Land) pictures? Well … Governor Macquarie visited Van Diemen’s Land on two occasions: in 1811 (before Lycett arrived) and in 1821 (a few months before Lycett left for England). I love connections and so I was pleasantly surprised to discover that Governor Macquarie named the Austins Ferry area as Roseneath when he visited Van Diemen’s Land in 1821. Did the Governor make drawings and bring back sketches? This is doubtful. It is more likely that others went to Van Diemen’s Land at the Governor’s request, brought their sketches back to Sydney and that these were shown (perhaps some were given) to Lycett.

I wondered whose sketches, paintings or etchings Lycett saw, and then ‘used’.Two people with drawing skills have been suggested: George Evans and James Taylor.

First, let’s consider George Evans.

In the first two decades of the 1800s, Governor Macquarie sent surveyor George William Evans to Van Diemen’s Land off and on a number of times for short trips to remeasure land previously granted (misconduct involved); various sources suggest different years so I am not sure exactly which years in the second decade of the 1800s Evans was in Tasmania; some suggestions are Sept 1812 to Aug 1813, 1814, July 1815 to 1817. Wikipedia suggests that on two occasions Evans was granted valuable acres of land near in the Coal River Valley near the town of Richmond outside the Greater Hobart Area.

According to http://www.daao.org.au/bio/george-william-evans/biography, at the end of 1818 Evans was able to resume office as Deputy Surveyor-General of Van Diemen’s Land. His travels around Tasmania are recorded in his Geographical, Historical and Topographical Description of Van Diemen’s Land… (London, 1822). One of his watercolour sketches of Hobart Town was used for the foldout aquatint and etching used as the frontispiece in the original edition. Another of the town was published by Ackermann of London as an independent print. Both depict Hobart as a thriving British colonial seaport town with court-house, commissariat store, St David’s Church, warehouses and numerous domestic dwellings in evidence. A surviving original (Dixson Library) shows a competent understanding of watercolour technique.

The website http://www.nla.gov.au/selected-library-collections/lycett-collection offered: ‘As well as being a competent surveyor and a resolute explorer, Evans was an artist of some note. His aquatint view of Hobart in 1820 was published as a frontispiece in his Geographical, Historical and Topographical Description of Van Diemen’s Land … (London, 1822; second edition, 1824; and a French edition, Paris, 1823). The original, with another aquatint of Hobart in 1829, is in the Dixson Library of New South Wales.’

Second let’s consider James Taylor.

Military officer, Major James Taylor, arrived in Sydney in 1817 with the 48th Foot Regiment. Taylor produced a number of paintings and prints throughout his tours and his panoramic works of Sydney were particularly popular. He travelled to Van Diemen’s Land with Governor Macquarie in 1821. On 15th February 1822 he sailed to Britain with the Macquaries on board the Surry. Only 50 people including the crew were on board for this 5 month trip around Cape Horn and it is easy to speculate that Macquarie and Taylor would have talked about Lycett.

Comparison of art works

I decided that comparing the works of the three artists Evans, Taylor and Lycett might help me to understand where Lycett’s Tasmanian images came from. Unfortunately, I have not been able to locate sufficient of the work of Evans and Taylor to make a solid comparison despite knowing Lycett’s work very well (having worked in the Newcastle Art Gallery for a number of years in the presence of a substantial collection of Newcastle district related images by Lycett). Nevertheless some images for Evans and Taylor are available.

Examples of Lycett’s art

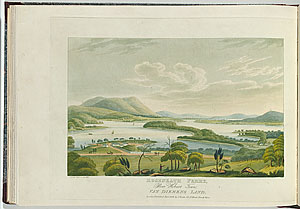

Below is an image of Lycett’s etching (see below) titled Roseneath Ferry near Hobart Town, Van Diemen’s Land dated 1 December 1824 (two years after Lycett left Australia). The etching was published as plate number 4 in Views in Australia or New South Wales and Van Diemen’s Land Delineated. London: J. Souter, 1824. This etching is held in the collection of the National Gallery of Australia in Canberra. Lycett is looking across the Derwent River from somewhere above the western shore and southwards so that the ‘hill’ in the distance to the left of the picture is Mount Direction (you may recall I walked past this as I passed the Bowen Bridge on my way from the suburb of Risdon to the suburb of Otago Bay on the eastern shore).

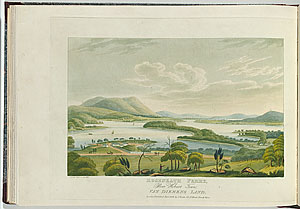

The image below, also by Joseph Lycett, is another hand coloured etching, this time from the viewpoint of the eastern shore. The title is View of Roseneath Ferry, taken from the Eastside, Van Diemen’s Land and it was produced in 1825 (when he was already living in England). One of the edition of this etching is in the collection of the National Gallery of Australia in Canberra.

The image below is Distant View of Hobart Town, Van Diemen’s Land, from Blufhead Plate 28 from Views of Australia or New South Wales& Van Diemen’s Land, published by John Souter, London, 1824-25. This handcoloured aquatint and etching is held in the Joseph Brown Collection of the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne.

Examples of George Evans’s art

The image below comes from http://www.abc.net.au/news/2014-08-22/1819-slnsw-south-west-view-of-hobart-town-1819-george-william-e/5689410 It is titled South West view of Hobart Town and dated 1819

The image below comes from http://www.acmssearch.sl.nsw.gov.au/s/search.html?collection=slnsw&meta_e=350

Hobart Town, Vandiemen’s Land. 1828 At lower left is printed “G. W. Evans. Pinxt.”; at lower right “R.G. Reeves. Sculpt”; underneath title “Published 1828, by R. Ackermann, 96 Strand, London” he image is from the collections of the State Library of NSW.

Examples of James Raylor’s art

I could find no image by James Taylor that was related to Van Diemen’s Land. I only found two New South Wales images.The image below is from http://www.afloat.com.au/afloat-magazine/2010/july-2010/Lachlan_Macquarie#.VHAuwPmUdqU and titled Panoramic view of Port Jackson c.1821

The image below, from http://www.powerhousemuseum.com/collection/database/?irn=326892 is an aquatint of Port Jackson and Sydney dated 1824.

This panorama of Port Jackson and of the town of Sydney was taken from a hill near the Parramatta River, was produced with ink on paper by Major James Taylor, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia, 1820, then engraved by Rittner et Goulpil, Sydney / Paris in 1824. The Powerhouse Museum (Sydney) provided the following information:

‘Statement of significance

In 1820 Major James Taylor created a series of watercolours on paper which, when joined together, formed a panorama of Sydney. When he returned to England in 1822 (did Taylor and Lycett travel on the same ship? – more research required) Taylor arranged for the engraving and printing of a three sheet panorama based on his watercolours. Known as ‘Major Taylor’s Panorama’, this is one of the most informative depictions of Sydney in its early years. Taylor, a topographical draughtsman attached to the 48th Regiment, arrived in 1817 when Sydney was thriving and Governor Macquarie was trying to turn an ‘infantile’ penal colony into a ‘civilised’ society. Taylor’s pictures were intended to be a record of that change. The view, taken from Observatory Hill, encompasses Sydney Harbour from the Heads to Lavender Bay, showing many of the major buildings of the day.

Convicts can be seen cutting the sandstone which provided building material for Sydney’s expansion. The many fences indicate gardens and a respect for private property. The harbour is filled with trade and military ships. Government House and its stables can be seen set in Governor Macquarie’s private park called the Demesne. Much of this park still survives as the Botanic Gardens and the Domain. This area contrasts markedly with the small cottages in the middle ground which were typical of many in The Rocks. They were often occupied by convicts and their families who were encouraged to develop ‘respectable’ habits like gardening in their spare time.

A prominent building is the Military Hospital, built in 1815, where patients can be seen dressed in long coats. On the horizon are the impressive buildings of Macquarie St, including St James Church, the Hyde Park Barracks and the General Hospital. To the right of the Military Windmill is Cockle Bay, later called Darling Harbour. The land beyond is the Ultimo estate owned by the surgeon John Harris. To the far right are the windmills that gave rise to the name Millers Point.

Topographical artists often included indigenous people in their work. These images were intended to educate European viewers about the appearance and customs of the ‘natives’, but such depictions were informed by symbolism and ideology rather than a representation of reality. In Taylor’s panorama Aborigines stand amid uncultivated bush, in contrast to Europeans who are clearing and grazing the land. When the British took possession of New South Wales they argued that, as the Aborigines did not ‘work’ the land, they did not own it. This supported the notion of ‘terra nullius’ or nobody’s land. Taylor’s representation is a graphic rendering of that argument.

Production notes

The engraving is based on watercolours by Major James Taylor. Taylor was a topographical draughtsman attached to the 48th Regiment. He arrived in Sydney on the convict transport Matilda on 9 August 1817. He accompanied the Macquarie’s on their tour of Tasmania in May and June 1821 and some of the Tasmanian views in Joseph Lycett’s Views are probably based on Taylor’s drawings. Taylor received some training in draughtsmanship as part of his military studies and like other military and naval officers, was interested in his surroundings and recorded them in watercolours. Little of Taylor’s work survives, notably the originals of this view of Sydney Harbour. This image is held in the Powerhouse Museum collection.’

My conclusion

Lycett’s style is quite different from each of Evans and Taylor so it is difficult to attribute the work of one or the other as being the ‘aid’ to Lycett’s Tasmanian etchings.

There are three possibilities.

- Lycett took the shape of the landscape around Roseneath from Taylor’s drawings. I am guessing that since Taylor accompanied Governor Macquarie to Van Diemen’s Land in 1821, he probably went to Roseneath with the Governor on the day that Macquarie named Roseneath. It is conceivable Taylor rushed up a few sketches and it is these that either Taylor showed or gave Lycett, or Taylor gave to the Governor who showed or gave them to Lycett. Perhaps the three of them met in London on arrival in 1822?

- Lycett had access in Sydney to Evans maps of the land, and using their flat two dimensional nature, he fabricated a three dimensional landscape. If indeed he worked in this way, then the odd shapes of some topographical features of the landscape in Lycett’s pictures from and towards Roseneath can be explained.

- Lycett had access to both Taylor and Evans work and amalgamated them to create a fictional but partly realistic depiction of Tasmanian sites. Lycett’s history is one of creativity, so sticking to the facts of the situation wouldn’t necessarily be important.

Incidental extra

In conclusion, there is one connection between the current Hobart and the Derwent River and the early 19th century Joseph Lycett – which could never have been foreseen. I discovered that Lycett was on the list of prisoners that sailed to Newcastle on 8 July 1815: the name of the ship was the Lady Nelson. Pride of place on the today’s wharf at Hobart is a training sailing replica, the original having been stripped, burnt and sunk in 1825.

-42.780404

147.252277