I lived the walk along the Derwent with a vital obsession but, after so many months intensely engaged on other projects, now some of the details are vague. To re-immerse myself into the experience, I am writing this post.

In addition, I suspect it will be a great help to people who have become followers of my blog during the past 6 months. Despite my inactivity, it surprises me how many visitors and views the blog gets daily, how many different posts are read, and how many different countries around the world are represented.

In August 2014, from an impulsive unplanned idea, I took a bus to a spot near the mouth of the Derwent River on the eastern shore, walked to the sea then retraced my steps and began the walk towards the source of this great river approximately 214kms inland. On day trips, and around other life commitments, I walked in stages along the eastern shore until I reached the Bridgewater Bridge which crosses the Derwent approximately 43 kms upstream.

Instead of continuing inland, I crossed the bridge and headed back on the western shore towards the southernmost mouth of the River. Most of the walks along the eastern and western shores between the sea and the Bridgewater Bridge were along designated pathways, although some informal track walking, road walking and beach walking was required during my trips.

Then I returned to the Bridgewater Bridge and began the journey inland expecting only to walk on the side of the river that made passage easiest. I had no intention to walk both sides from this point onwards in anticipation the landscape would be inaccessible for a number of reasons or particularly wild with dense and difficult forests. I walked to New Norfolk on the western/southern side of the Derwent but from then on, I switched from side to side. Using maps I determined where I must take up each new stage of a walk while switching from side to side, so that I could say I had traipsed the entire length of the Derwent River.

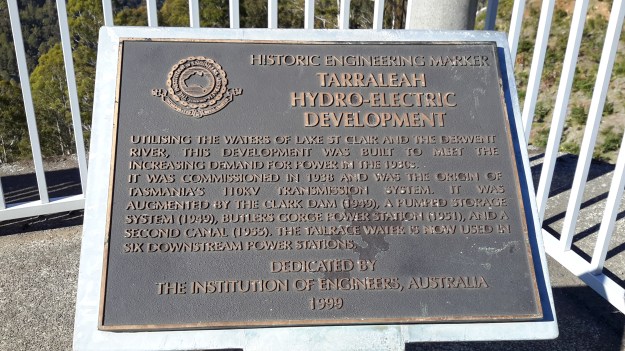

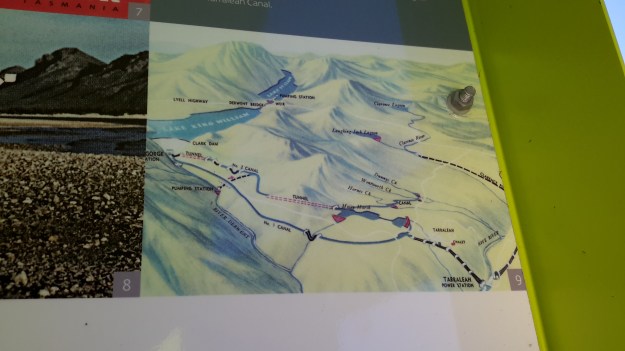

The farthest inland stages of my walk are easily defined. I walked from near the township of Tarraleah besides Canal 1 (along which is transported Derwent River water) above the actual River bed, past Clark Dam, and around majestic Lake King William to the township of Derwent Bridge. From there I followed the river to its source at St Clair Lagoon dam. In case some people believe the source of the Derwent is further inland, I walked onwards to the weir where the Derwent Basin empties into the St Clair Lagoon via passing the southern end of Lake St Clair.

Between New Norfolk and the area near Tarraleah, my walk beside the River was in country near townships (some of which were located at a great distance from the River) such as Bushy Park, Gretna, Hamilton, Ouse, and Wayatinah. This necessitated additional travel to or from the highway and roads, on which these towns exist, to reach the river or to return home from a walk along the river.

Inland, the water of the Derwent River is controlled by dams constructed to create hydro-electricity for Tasmania: I walked past them all. From the end of the river closest to the mouth, these are the Meadowbank, Cluny, Repulse, Catagunya, Wayatinah, Clark and St Clair Lagoon dams. Each of these has a bank of water behind them: Meadowbank Lake, Cluny Lagoon, Lake Repulse, Lake Catagunya, Wayatinah Lagoon, Lake King William and St Clair Lagoon. Most of these dams and bodies of water has a power station: Meadowbank Power Station, Cluny Power Station, Repulse Power Station, Catagunya Power Station, Wayatinah Power Station and Butlers Gorge Power Station. I was privileged to be shown around one of these power stations during one walk.

Water from the Derwent passes through two other power stations: Nieterana mini hydro and the Liapootah Power Station. I did not follow the trail of these Derwent River managed flows. The water from other locations inland passes through the Lake Echo Power station and Tungatinah Power Station then flows into the Derwent after power generation, thereby increasing the volume of water flowing downstream. I did not walk along these feeder rivers.

The few stages of the walks which have not been recorded in this blog, are in all the zone between Gretna and the area near Tarraleah – a stretch of perhaps 120 km. I have written up and posted most of the walks in this zone, and now it’s time to add the missing sections.