This post provides a background on an extraordinary feature of the walk between Wayatinah and Catagunya Power Stations along the Derwent River. It is about one of the great surprises of this ‘walking the Derwent’ project and, as such, reminds me that even the most ordinary of explorations can unearth new discoveries (for those not familiar with an industry – in this case, the industry involved with penstocks).

Okay okay okay I know some readers will have rolled their eyes wondering what a penstock is. A penstock is a very large pipe that is laid downhill through which water falls at high speed to an electricity generating power station. Refer to photos in some of my earlier posts such as: Derwent River water passes via the township of Tarraleah .

My typical experience of penstocks, as conduits for water gushing into electricity generating power stations, is of massive steel structures. I suspect this would be the expectation for others who have seen Tasmania’s penstocks only from the vantage point of our highways. For people like me, the wooden penstocks feeding Wayatinah Power Station are astounding and therefore I thought it would be of value to undertake some research and learn more. Andrew’s photo below shows the wooden penstocks emerging from an underground tunnel and sloping down towards the Wayatinah Power Station.

The questions which come to mind include, are there any other wooden penstocks in Tasmania, what wood is used, when were they built, why weren’t they built with metal, who built them, how effective are they, and what is their life span. In my research a constant term was ‘stave’. A stave is a narrow length of wood with a slightly bevelled edge to form the sides of barrels, tanks and pipelines, originally handmade by coopers.

After a little research I now know that wooden penstocks are not unique to Tasmania and have been built in a number of countries including Britain, Canada and the USA. For example, wooden penstocks were built for hydroelectric facilities in Lincoln County, Wisconsin, USA as shown in this article. This web site contains a great deal of construction and other information which I imagine is similar to that for Tasmanian wooden pipelines, and therefore worth reading. The photo below, from that website, shows redwood penstocks at the Thomson Hydroelectric Station in eastern Minnesota, Wisconsin.

The website answered some of my questions: “Why wood? First and foremost, keep the wood thoroughly wet and it will not rot. If there is an issue, it has to do with the quality of the metal bands. Expansion joints are not required as the wood absorbs the water and expands. Steel restraining bands are used and the wood will expand against those. The metal bands are used only to provide strength. Even when they corrode and lose their strength, the wood will hold together and the bands can be easily replaced. The carrying capacity exceeds that of metal pipe, in large part because the interior walls remain smooth and do not form tubercles. The wood components are easily transported to the sites, which can be remote. No massive hoisting apparatus is needed. They do not require concrete foundations, but “float” on the gravel. The wood is easy to bend, so the contractors can follow a more natural contour; for example, bending around curves. There is no need to cover them. The wood has natural insulation. They can last for 40-50 years. Simple carpentry can be used for repairs. Assembly is easy.

Why do we see so any leaks? Leaks do occur at the end of a stave, at what is called the butt-joint, most often when combined with a breakdown or severing of a steel band at that point. In addition, steel plates are sometimes placed in the slots at each stave end, and these steel plates can corrode. Also, some erosion can occur at the end of a stave, and develop into a hole. In this instance, the steel band in that area might corrode and sever, and the pressure of the water inside might break off a section of the stave, however small. Metal corrosion also sets up a mild acidic condition. The acid can degrade the wood. There can be a breakdown in the staves when the water pressure inside varies a lot. You will seldom see wooden penstocks for example in positions where turbines can vary the water pressure output in large degrees. This creates what is known as the hammer effect which can beat up a wooden penstock quickly. It’s best to try to keep the inside water pressure as even as possible. This said, small leaks can self-repair as the wood expands. Even large breakdowns in the staves can be repaired. In most instances, the leaks are tracked closely and there is very little risk of a catastrophic failure. “

The hole in a penstock and the story of its repair speedily within one week for the Jackson Hydro Station in New England, USA can be seen here. Another rupture coverage, this time in Quebec, Canada is covered here. I was surprised when this website included photos of other wooden penstocks around the world including a photo of one of Tasmania’s wooden penstocks. It looks remarkably like Wayatinah’s penstock, and there are outbuildings in view and some dates as well. Perhaps a blog reader can make a more accurate identification.

It seems there are only two Tasmanian power stations being supplied by water flowing down wooden penstocks: Lake Margaret Power Station (not on the Derwent River) and Wayatinah Power Station. Wikipedia explains the situation in relation to the Lake Margaret Power Station here. For more information refer to the fact sheet for Upper Lake Margaret Power Station, the fact sheet for the Lower Lake Margaret Power Station, and a note regarding Innovation and heritage feature in Lower Lake Margaret redevelopment. Photos of the pipeline can be seen in Lake Margaret Power Scheme A Conservation Management Plan. I found the photos on pages 11 and 19 particularly helpful with pinpointing the location.

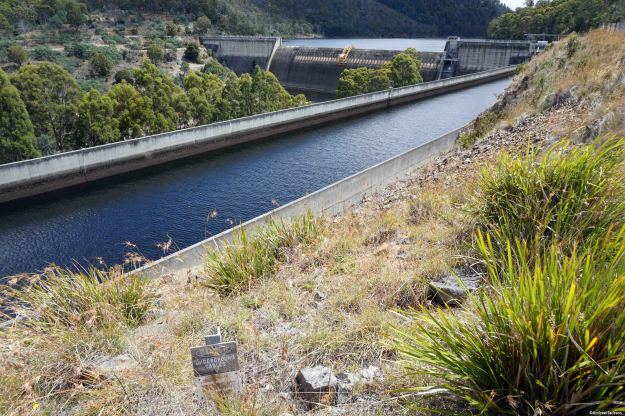

In relation to the wooden penstocks feeding the Wayatinah Power Station, a You Tube video is worth watching. Page 25 of the booklet ‘The Power of Nature’ includes a photo of the woodstave penstocks at Wayatinah. Other informative photos of dams and power stations and penstocks associated with other parts of the Derwent River are also presented. Most are glamour shots taken from excellent locations and, after the gritty often basic photos which I have taken, these make the extraordinary engineering feats look even more magnificent and significant. This website offers the following information: “Wayatinah is the sixth station on the Nive/Derwent cascade and is downstream of Liapootah HPP. Water is supplied from a small storage lake called Wayatinah Lagoon and diverted into a 2 km tunnel to two 1.3 km low-pressure wood stave pipelines. Finally, water drops 56 m through three steel penstocks to the powerhouse.”

Now the scene is set for the story of the walk between Wayatinah and Catagunya Power Stations.

During the many vehicular crossings of the Bowen Bridge that I have made, I could never see where it would be possible to climb down and be under the bridge. Nevertheless I felt there must be a way.

During the many vehicular crossings of the Bowen Bridge that I have made, I could never see where it would be possible to climb down and be under the bridge. Nevertheless I felt there must be a way.