A recent blog posting provided the ‘story’ of how I imagined a walking stage would progress along one section of the Derwent River. On paper, such visualisations have acted as a planning tool to remind me of the potential challenges ahead and the work I needed to do to make sure I was able to have a safe walk within a reasonable time frame. Another ‘big think’ happened in relation to the walk between Wayatinah and Catagunya Power Stations.

In the photo below, water gushing from the Wayatinah Power Station adds to the volume of Lake Catagunya near its western extremity.

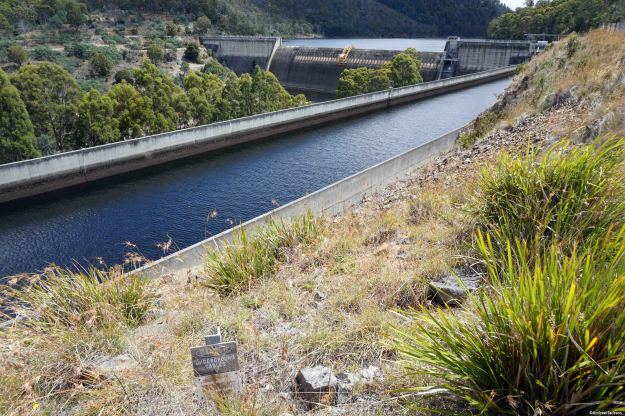

This expanse of water, fed by the Derwent and Florentine Rivers further upstream, extends approximately 7 -8 kilometres as a substantial water storage holding until it reaches the Catagunya Dam wall and then passes through the Catagunya Power Station at the eastern end of the Lake. Earlier walks had taken me to both hydro electricity generating power stations, and during one walk I was privileged to be shown over the remote and isolated Catagunya Power Station complex.

How to tackle the distance between the two locations? Should I start my walk from the eastern or western end? Should I walk on the southern or northern side of the Lake? The terrain to be covered included private property so what permissions needed to be acquired and from whom?

At first, I inspected the last official map printed by the Tasmanian government, the 1993 map titled ‘Strickland 4630’ in combination with perusing the Google Earth map for the same territory. In addition, I used my on-the-ground first-hand knowledge of the terrain and the vegetation at both ends of the stage from having visited in association with other walks, and aerial photos taken early during this Walking the Derwent project.

Michelle’s photos show Wayatinah Power Station in the distance near the western end of Lake Catagunya, a section of the curved shape of the Lake, and Catagunya Dam and Power Station. Each photo clearly shows the incline from water level to the plateau above.

My aerial photos show Wayatinah Power Station behind an expanse of Lake Catagunya, the major inlet close to the eastern end of the Lake, and the Catagunya Dam and Power Station complex. The density of the forests and the hilly terrain are clearly shown.

Chantale’s aerial photos show the inlet, fed by Black Bob’s Rivulet, near the eastern end of the Lake.

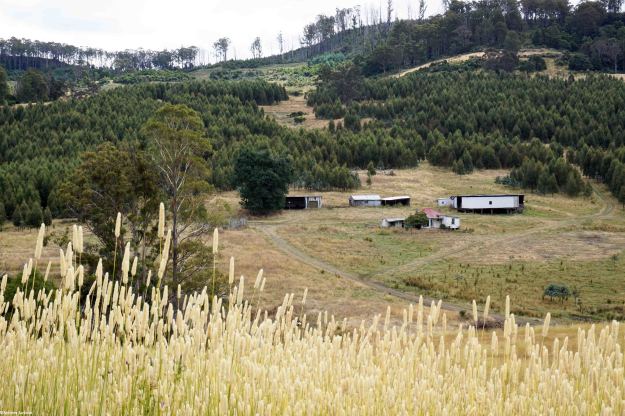

What I had seen on the ground and in the air was not what maps showed. For example at the Catagunya end, massive comparatively new pine plantations had swept across hills where natural bush once grew. This meant that a mesh of unmapped forestry roads would have been built and that these would make navigation confusing without a compass and/or GPS equipment.

Clearly the edges of the Lake were/are exceptionally steep and if my walks elsewhere in the region were used as a guide, the slopes would be a mixture of dense wet rainforest tangled around partially hidden rocky outcrops. Both sides of the Lake have sections which rise over 200 metres within half a kilometre. All indications are that walking at water level would be impossible. If Plan A to walk alongside the Lake wasn’t possible, what should be Plan B?

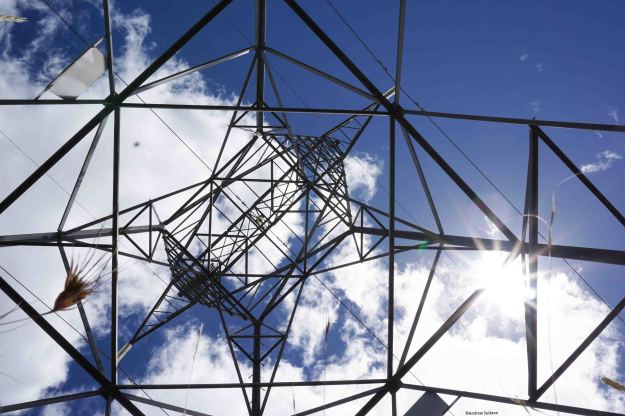

On the northern side, skyscraper-high electricity transmission structures with their connecting wires have been installed in a straight line from the Wayatinah to Catagunya Power Stations and located roughly at the top of the steep incline from the Lake. I felt this line would be the best option for progress. During construction, an area of less than hundred metres wide was cleared to create a pathway for vehicles to use. Perfect for easy walking? Reflections on past experiences suggest not. This is rainforest territory and as a constantly regenerating living organism, I realised that I should expect the forest to have begun to re-establish itself. I recalled walking along the ‘cleared’ transmission lines area through the most challenging vegetation on unseeable uneven ground at the northern end of Lake King William. It was slow, tedious work where a snapped ankle was always a possibility.

Thinking of the Wayatinah to Catagunya leg, I made a note to contact TasNetworks to see whether their clearing program had reached this transmission area, and whether I could hope for a reasonably straightforward walk along this line. Google maps indicate a vehicular road leaves the Wayatinah Power Station area and continues eastwards for the first half a kilometre of the 7 km line of towers. It seems to stops short of the first heavily forested gully that cuts deeply through the landscape and which contributes water downhill to Lake Catagunya. 400 metres past that obstacle is a new similar impediment to smooth walking. A third such impasse waits a further 400 metres eastwards. In advance of the walk, it was easy to imagine the vegetation would be slippery with dripping water from the plants, the light levels amidst the tightly packed vegetation in the ravine would be low, and the flow of water over the centuries would have exposed rocky outcrops that would make descent and then ascent on the other side of the creek time consuming and treacherous. Until in the presence of each ravine, judgements could not be made as to whether to walk inland to skirt around the worst of the cuttings or whether it might be possible to descend and ascend on the other side safely and with my backpack still attached to my back.

Approximately half way through the walk after the three creeks, an undulating plateau with a lower gradient should be a welcome change for a few minutes before the terrain drops down to Bushman’s Hill. I would expect this site to be seriously forested and not to offer grand views of the Lake, and I would expect a mesh of unexpected and unpredictable forestry and Hydro Tasmania roads across the land. Ahead the land drops away rapidly, is crossed by another deep creek cutting, until it reaches a significant inlet body of water that is more than 100 metres wide. This water extends inland for over one kilometre. Into this length of water flows Black Bob’s Rivulet which extends for many kilometres north west of this area. There would be no choice but to walk around this obstacle and cross the Rivulet where possible, until a connection with Catagunya Road could be made. The degree of deviation will depend on the nature, location and extent of the plantation and natural forests.

Once on the Road, an easy gravel surface leads to Catagunya Dam and Power Station; perhaps 4 to 6 kilometres of road will need to be walked depending on the difficulty getting around the inlet. After panoramic photos are taken to record the Lake and it’s edges, then a 7-8 km walk to the locked gate at the Lyell Highway will conclude this leg of the walk along the Derwent.

All up, and at the best, perhaps 18-22 km would be walked in this stage. If substantial rerouting around the creeks was required then the distance would be much longer. Fundamentally, I imagined this was a walk of clambering up and descending steep forested hills relentlessly. Depending on the density of vegetation in the ‘cleared’ transmission line area and then the difficulties crossing the creek cuttings, at best this walk might take 10 hours. At worst, and probably realistically, it will require sleeping out overnight, and therefore I will walk with the full complement of camping gear.